From the mid-1980s, articles about command approaches became a feature of many military journals. Most veered towards an unproven view that what became known as ‘the Manoeuvrist Approach’ and, to complement it, a command approach now designated Mission Command, were ‘a good thing’. Although these were codified in various doctrinal publications, their adoption was not a ‘given’: the landmark Design for Military Operations: The British Military Doctrine of 1989 did not use either term.[i]

These developments were based on a limited theoretical model, which typically differentiated between just two command approaches. These had first been described in the late nineteenth century German debates regarding the implications for command of dispersed formations:[ii]

- Auftragstaktik: Commanders set out their intent, but leave the means of its achievement to their subordinates’ initiative, based on the latter’s better knowledge of the local situation.

- Befehlstaktik: Commanders rely on their better knowledge of the wider context, so issue detailed orders that their subordinates must follow rigidly, regardless of how events unfold.

When these concepts inspired anglophone doctrine, they were often reduced to mechanical lists of ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’, largely divorced from the human circumstances to which they relate. In practice, the widespread perception that Mission Command was ‘just another’ managerial concept, combined with the existence of seemingly permitted exceptions, allowed significant deviation from endorsed practice.[iii]

With hindsight, the near absence of consideration of other command approaches, or exploration of how particular command approaches develop and why they persist, was a striking feature of this debate. There was also little rigour around why Mission Command was thought to be the right choice.

This article describes an empirical typology, or classification, of command approaches. It does so in order to enable what is perhaps an overdue examination of the variety of command approaches and of their relative merits. The typology relates to a fundamental feature of warfare: friction. It is presented here recognising that many factors affect the preference for, and application of, particular command approaches by different armies. These factors, which may include political expectations, cultural tunnel vision, and technology, merit further discussion. Presenting the typology here may encourage such deeper examination of the subject.

No attempt is made to define ‘command approach’: if it looks, feels or smells like a command approach, then it is a command approach. In this context, ‘command approach’ is taken to encompass both managerial practice and leadership style, though the focus is more on the technical than the interpersonal. The variability of possible definitions underlines how poorly the whole subject is understood.

Towards a Model of Command Approaches

From the late 1980s, recognising the weak conceptual foundations of these developments, the late Michael Elliott-Bateman, with his postgraduates (including this author) at the Department of Military Studies, University of Manchester, explored issues related to command approaches in order to suggest a more robust model.[iv]

Central to their argument was the proposition that different armies perceive combat in fundamentally different ways. Some see it as inherently structured, others as essentially chaotic. This perception is expressed in the command approach that an army generally employs. Armies that understand combat as inherently structured seek to reduce friction by imposing control of the battle from above through ‘Restrictive Control’. Conversely, armies that consider it essentially chaotic aim to reduce friction by maximising subordinates’ initiative to achieve the overall intent – ‘Directive Command’.[v] It was suggested the British Army generally demonstrated a preference for Restrictive Control, while the German Army leaned towards Directive Command. Exceptions existed, of course, such as Major Chris Keeble’s encouragement of initiative at Goose Green in the Falklands War of 1982 and Alfred von Schlieffen’s insistence on rigid obedience to orders in the 1890s. However, these examples served to prove the rule.

Having identified a conceptual basis for command approaches, the group identified further variations, such as ‘Umpiring’. Here, commanders set out their intent and leave the means of its achievement to their subordinates’ initiative, yet do not intervene even when they see those subordinates acting in ways that will not deliver the intent. For example, Sir Ian Hamilton felt unable to get involved when Aylmer Hunter-Weston’s initial landings at Gallipoli in April 1915 went awry.[vi]

But although this model represented an important conceptualisation, it remained largely descriptive, due to the limited connection with friction. In fact, the wider military literature contains surprisingly little discussion of the interaction between command and friction, in the Clausewitzian sense of ‘the force that makes the apparently easy so difficult.’[vii] Although it is all-pervading in human conflict, and hence a major factor to be accommodated, Martin van Creveld commented, ‘Save perhaps for the occasional intercepted or misunderstood message or the broken-down radio, it is indeed possible to study military history for years and hardly notice that the problem exists.’[viii] The deeper model of friction developed by a group assembled by Stephen Bungay, a director of the Ashridge Strategic Management Centre,[ix] is therefore of particular importance, as it enables the initial model of command approaches to be developed into the explanatory typology presented here.

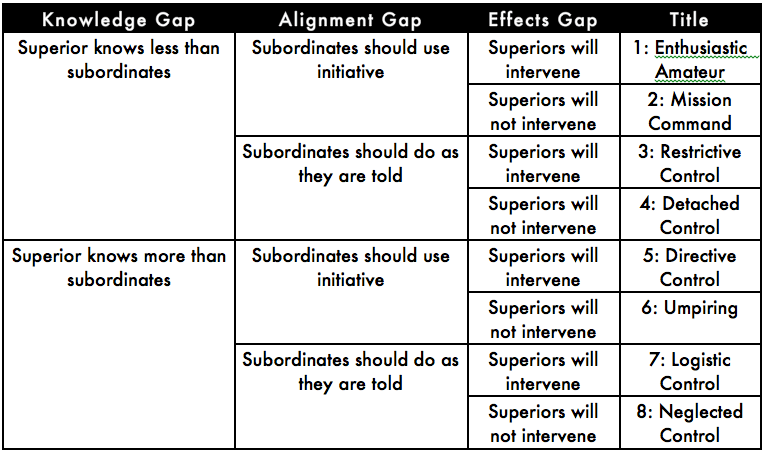

Bungay’s group adopted Clausewitz’s understanding of friction as a basic characteristic of the (military) environment, which any successful army therefore needs to address as a matter of routine. They noted that friction manifests itself in three areas: the difference between what is known of the real world and what the commander would like to know (the Knowledge Gap); the difference between what commanders wish their subordinates to do and what they actually do (the Alignment Gap); and the difference between what commanders expect their actions to achieve and what they actually accomplish (the Effects Gap).[x] This is expressed graphically in Figure One.

FIGURE 1: Stephen Bungay’s Three Gaps Model

How the three gaps are generally accommodated by commanders (and their staffs and command processes) allows us to understand command approaches.

- Knowledge Gap: Commanders may act as if they know more about the situation in the real world than their subordinates, or less than them.

- Alignment Gap: Subordinates may use their initiative to fit their actions to the real situation, or may do precisely as they are instructed from above.

- Effects Gap: Commanders may intervene in subordinates’ actions, in order to rectify perceived differences between what they are doing and what the commander wishes to achieve, or may desist from doing so.

Combining the thinking of these two groups allows a new typology of command approaches to be developed, based on these representing different approaches to reducing friction, as differently perceived by different armies.

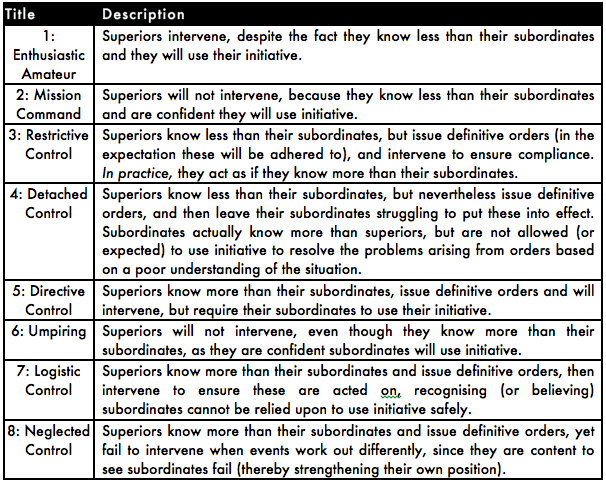

Knowledge, alignment and effects can be considered as three broad ‘either/or’ axes, which allow us to generate a simple model having 2x2x2 (that is, eight) permutations. These are listed at Figure Two and described in more detail at Figure Three.

FIGURE 2: Eight Permutations

Describing the Command Approaches

The names used here are chosen for ease of reference and, where possible, avoid negative perceptions. The aim here is to identify the full typology, rather than to make judgements regarding relative effectiveness. Permutation 8: ‘Neglected Control’, is negative, which is insightful in relation both to this permutation specifically and the list in general. It may describe a situation in which a superior seemingly deliberately sets up their subordinate(s) to fail. Despite seeming unlikely, it may perhaps reflect situations where allegiances are uncertain and political considerations outweigh immediate military objectives, such as in a civil war or the Italian Army of 1940-42. The ability of the model to generate such permutations illustrates its value and (perhaps) power.

FIGURE 3: Contrasting Command Approaches

The eight permutations can be considered as follows:

- ‘Enthusiastic Amateur’ might be typical of the early stages of a large civil war (such as the American Civil War or English Civil War), where most commanders act enthusiastically and in accordance with the perceived common good, but where command issues relating to decentralisation have not yet been agreed.

- ‘Mission Command’ may be considered the default preference of the German Army for more than a century. It is widely held to be appropriate to the armed forces of many developed states, but requires significant levels of responsibility, initiative and training on the part of subordinates.

- ‘Restrictive Control’ may arise where a small professional army has experienced rapid expansion at the start of a major war, such as the British Army in 1914-16 and the American Army in 1941-42. It may also reflect arrogance on the part of superiors, where the potential ability of subordinates to use initiative is discounted, perhaps as a consequence of the selection and training of commanders.[xi]

- ‘Detached Control’ is probably unthinking and may reflect inadequate training of superiors. They have been taught command and staff processes (perhaps by rote), but understand neither their own limitations nor the ability of subordinates to get things done. Critically, it may be what is actually practised (as opposed to intended) in modern western armies. The fault may lie in overly-prescriptive doctrinal pamphlets (and training systems).

- ‘Directive Control’ can be seen as an expression of the German approach of ‘the commander at the Schwerpunkt’. It suits a situation where the senior commander takes personal control at the critical point, but has subordinates with the training, education and experience to display initiative. It is also perhaps appropriate in large-scale operations where the big picture is more important than local detail, such as the D-Day landings in Normandy.

- ‘Umpiring’ can be seen as careless (failing to take responsibility to intervene when things go wrong) or as Mission Command gone wrong (failing to pass relevant knowledge down to subordinates, so they can use initiative effectively). It may be well-intentioned, sometimes resulting from command relationships that are too familiar or insecure, such as where commanders hold the same rank as their subordinates. It may have been characteristic of formation-level commanders in the pre-1914 British Army.

- ‘Logistic Control’ is a seemingly unobjectionable name for a very highly centralised command system. It might be representative of the position sometimes achieved in modern high-technology warfare, where sophisticated intelligence systems may (appear) to give commanders more information than can be gained by their subordinates. The term Logistic Control was coined to suggest that, in the first instance, subordinates (and formations) are treated largely as inanimate objects to be pushed around, like boxes to be delivered. The Soviet Army may have aspired to this approach in the 1980s.

- ‘Neglected Control’ was mentioned above. An alternative explanation is personal or cultural avoidance of responsibility. As with Umpiring, the commander may not feel his responsibility extends to correct problems at lower levels, even though this may prejudice mission success. Whatever the case, this describes behaviour few would describe as professional.

Connecting the Command Approaches

Another way of thinking about the model is in terms of space or volume. If knowledge, alignment and effects are considered axes at right angles to each other, then a commander’s (or army’s) command approach can be seen to lie in a space with eight possible extremes, as expressed in Figure Four. A real cube, with names written on it, makes visualisation easier.

FIGURE 4: Command Approach Cube

The cube reveals that (for example) approaches 2 (Mission Command) and 6 (Umpiring) are in some ways quite similar. In both cases, superiors will not intervene and subordinates display initiative. They differ only in that in Umpiring the commander ignores the fact he knows more, while in Mission Command he recognises he knows less. This implies it is relatively simple (although not necessarily easy) to move from one approach to another, either as an individual or as an organisation. The first step is realising the different approaches exit. The second is understanding what separates them. The third is engineering the move.

The cube indicates four pairs of approaches are the exact opposite of each other, eight pairs are adjacent to each other (sharing two factors) and eight pairs that share one factor (lying diagonally opposite each other on the same face). It is probably no accident that Mission Command and Logistic Control are opposites: they are the natural successors to Auftragstaktik and Befehlstaktik. Both can be recognised as entirely logical responses by professional commanders and armies to very different circumstances. They can now be seen as direct opposites. The cube also tells us that all the other approaches have at least one factor in common with both of those opposites. It also suggests an army could:

- Conceptually move from its present preferred approach to several others with just one step.

- Drift away from its preferred or official approach relatively easily, by sliding inadvertently along one of three axes.

Either case might be good or bad. For example, in the early 1990s, the British Army attempted to move towards Mission Command by, first, enunciating the alternatives and, next, moving from something like Umpiring to something like Mission Command (described at the time as ‘Auftragstaktik with Chobham Armour’).

A Note of Caution

The model, and particularly the cube, suggests there are eight precisely-defined alternative approaches. Clearly, that is simplistic. Not least, different human institutions, with different cultures and histories, do not behave in the same ways, and so different armies espousing Mission Command do not practice it in identical ways.[xii] The model, and the cube, should be taken to indicate there are, in practice, an infinite variety of command approaches. The eight permutations are simply illustrative places on that continuum, representing zones of similarity (as, for example, between the German and Israeli practice of Mission Command).

The model suggests that commanders and armies can move between permutations. It may, in due course, suggest why that might occur. The environment will typically be one of high stress (such as during a conflict or operation). Linking back to the earlier Manchester work, the model also suggests why some personality types may be predisposed to certain command approaches. Finally, the model may indicate factors facilitating or hindering armies seeking to move from one approach to another. Such factors may include officer training, the peacetime social environment, and experience of actual conflict.

The model is inevitably a simplification. Perhaps its most obvious shortcoming is around the Knowledge Gap. Does that gap indicate the commander actually does know more or less, or that he acts as if he does? Does it refer to knowledge of the wider context or of the local situation faced by each subordinate? Or to the relative importance of context and situation? Those questions denote several possibilities, and there are probably more. When linked to the Alignment Gap, they demand consideration of whether superiors are more capable of deciding what to do at lower levels. The plan for the first day of the Somme in 1916 assumed they did. The result was tragic.[xiii] But, given pitiably low levels of training on the part of subordinates, the assumption might be correct. Yet a commander would typically be poorly placed if he were to attempt to make every decision on behalf of his subordinates. The second- and third-order effects of delegating responsibility, not least on motivation and display of initiative, should not be discounted.

The model has implications for commanders and command systems, including the need for information to flow through the system, for trust between commanders and subordinates, and for training, not just before operations but also learning through the conduct of operations.

Command approaches are generally poorly studied, and hence poorly understood. They have emerged as a result of the military and human conditions that exist in armies and in the conflicts they undertake. It is better to understand how and why they have evolved, and their strengths and weaknesses, than to brand them as inherently ‘right’ or ‘wrong’.

Concluding Thoughts

Focusing on three major variables (superior knowledge, display of initiative, and intervention) suggests a model of eight broad command approaches. The variables are chosen from an analysis of the command process and its interaction with friction, specifically the gaps between reality, planning, and action. The model appears to describe much of the variation of command approach noted in history.

It is simplistic to say Mission Command is always right. It is more sensible to say, for the armies of developed nations, Mission Command generally best supports the achievement of military objectives in an environment that is inevitably human, complex, and dynamic. It is, however, entirely understandable that other armies might prefer other approaches. They might, for example, operate in conditions where their subordinates are grossly untrained, poorly motivated, or politically suspect.

The real benefit of the model is not to underpin a call for Mission Command. It is to assist the understanding of command approach, and ensure alignment between the approaches armies employ and the contexts within which these are employed.

[i] Design for Military Operations: The British Military Doctrine (Army Code 71451) (London: HMSO, 1989).

[ii] Stephan Leistenschneider, Auftragstaktik im preussisch-deutschen Heer 1871 bis 1914 (Hamburg: Mittler, 2002), pp. 98-122.

[iii] Eitan Shamir, Transforming Command: The Pursuit of Mission Command in the U.S., British and Israeli Armies (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), pp. 4-5.

[iv] The framework was most clearly set out in Martin Samuels, Command or Control? Command, Training and Tactics in the British and German Armies, 1888-1918 (London: Cass, 1995), pp. 3-5, and Spencer Fitz-Gibbon, Not Mentioned in Despatches… The History and Mythology of the Battle of Goose Green (Cambridge: Lutterworth, 1995), pp. xiv-xvi.

[v] This term has generally fallen from use, due to the (strictly incorrect) association of ‘directives’ with prescriptive written orders, and been replaced by ‘Mission Command’.

[vi] John Lee, A Soldier’s Life: General Sir Ian Hamilton, 1853-1947 (London: Pan, 2001), pp. 164-165.

[vii] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. by Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), p. 121.

[viii] Martin Van Creveld, Command in War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), p. 11.

[ix] I have benefitted greatly from the opportunity to discuss the ideas and concepts presented in this article with Stephen Bungay and with two other members of his group: Jim Storr and Aidan Walsh. The errors that remain are, of course, mine.

[x] Stephen Bungay, The Art of Action: How Leaders Close the Gaps between Plans, Actions and Results (London: Brealey, 2011), pp. 26-53.

[xi] Jörg Muth, Command Culture: Officer Education in the U.S. Army and the German Armed Forces, 1901-1940, and the Consequences for World War II (Denton, TX: University of North Texas, 2011), p. 80.

[xii] See Shamir, Transforming Command..

[xiii] Samuels, Command or Control?, pp. 124-157.